|

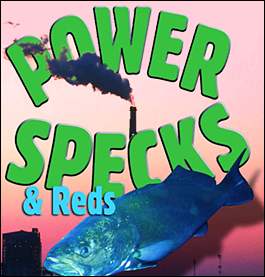

Power plant outfall canals consistently produce cold-weather redfish and trout action that's as hot as the water they release. Here's all you need to know to flip the switch and turn on the fun. Power plant outfall canals consistently produce cold-weather redfish and trout action that's as hot as the water they release. Here's all you need to know to flip the switch and turn on the fun.

By Chester Moore, Jr.

It looked way

too cold to go fishing. A thin blanket of ice carpeted the ground,

and small flurries of snow drifted down from the gray skies. Had

I been in Minnesota this would have been prime time for ice fishing,

but heading into such frigid conditions in Texas earns scrutinizing

stares from onlookers.

"Only

a crazy man would venture into such nasty weather. You guys need

straight jackets," the man at the boat launch told us.

My cousin Frank

Moore and I smiled and mumbled some little white lie like "It

ain't that bad." But it's safe to say we both agreed

with the man as we headed out into the 33-degree, stinging cold

morning. We would have worn straight jackets if they could've

kept us warmer.

The only "good"

thing about the weather was there was no wind to speak of. The

water in the Neches River was as smooth as glass, so the 16-foot

aluminum boat glided across it with great ease.

When we reached

our destination it seemed as if we were in some sort of strange,

twisted, winter dream. Icicles dangled from the high lines above

as steam rose from the water. At times it was so thick and rose

so high that we had to slow down to a virtual crawl to avoid a

collision with the bank or another boat. Being only half-awake,

I kept thinking this might be some sort of strange purgatory,

halfway between fishing heaven and hell.

Finally, I

snapped back into reality when Frank motioned for me to stop as

we came up to a big chain that blocked the canal. In the middle

of the chain was a sign that read: "No Trespassing; Property

of Entergy Corporation." We had reached the outflow station

of the Neches River Entergy Power Plant.

"We should

catch some fish," Frank said as he dipped his hand in the

water. "The water's really warm, so they must be pumping

out a lot today."

This Energy

Plant is like several similar outfits along the Texas Gulf Coast.

The plant cools its turbines by pumping water from one canal and

expelling it to another. In this case, the water comes from a

marsh that borders the Lower Neches Wildlife Management Area near

Bridge City and exits into a canal that leads to the mouth of

the Neches River-both of which usually hold salty water during

winter.

Baitfish congregate

in such warm water during cold spells, making them a sort of buffet

for a host of large predators like redfish and speckled trout.

They're great for human predators, too, since the cold-blooded

fish become much more active feeders in these spots than in the

much colder surrounding waters.

Frank and I

were the only anglers present in the canal that day, but there

were plenty of fish there. In fact, we limited on redfish and

black drum and caught more than a dozen speckled trout.

Not bad for

fishing in an ice storm.

Warm-water

discharges come in many forms. They can be huge cooling plants

that spew out thousands of gallons of warm water a minute or they

can be small drainage pipes or culverts that have a very light

flow. Oftentimes chemical refineries will have small pump stations

that producea warm-water flow that diverts into underwater pipes.

Any of these areas can hold a surprising amount of fish, but it's

safe to say that the more flow and the warmer the water in comparison

to the surrounding water, the more fish there will be.

Fish are often

concentrated in such great numbers in these canals that they become

easy pickings. Galveston-area guide Capt. George Knighten says

that before limits were in place he remembers catching several

ice chests of speckled trout at a time at the HL&P (Houston

Lighting & Power Co.) outfall in Trinity Bay.

continued

page 1 / page 2

|