|

By Shannon Tompkins

Page 2

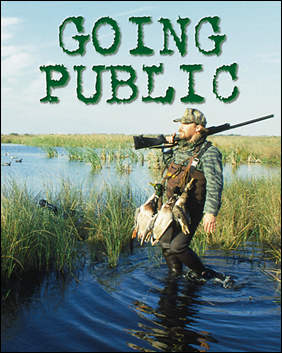

Success on public waterfowl

hunting areas is not guaranteed. It's not simply a case of throwing

a few decoys into the nearest pothole and waiting for the birds

to fall all over themselves trying to decoy.

Hunters who want to get the

most out of the public areas find they need to actually work at

it. Access to the areas may be monetarily inexpensive, but success

does have a cost. Hunters must invest considerable time, effort

and skill to best take advantage of the opportunities.

Each of the public waterfowl

hunting areas on the coast is different, with slightly different

habitat, regulations, means of access and duck populations. But

a few general tactics serve hunters well on all of them.

Some of those general tactics

and other advice culled from three decades of hunting ducks on

public areas include:

The main avenue to success

on coastal public waterfowl hunting areas is familiarity with

the place. No one can expect to boat or walk into a new area,

particularly in the dark of a winter morning, and expect to just

stumble upon the perfect pothole.

Pre-hunt scouting is absolutely

necessary. Knowing an area-learning its intricacies, the lay of

the land, how to reach certain places, how tides affect access,

etc.-above all other things determines how successful a public

lands hunter will be.

What to look for when scouting?

A place to hunt, of course.

The best ponds on public areas

seldom are the ones offering the easiest access. First, the "easy"

ponds are hunted hard, and birds tend to shy from them after the

first week or two of the season. Second, they attract a crowd.

Not good.

When scouting, try to find

isolated ponds relatively far from any easy access. Those ponds

seldom get heavy pressure, and because they aren't close to another

pond, hunters on them aren't prone to get crowded by another group.

The best way to locate those

ponds is to obtain a good map of the area before scouting. All

the refuges and state WMAs offer maps of the areas. Some even

have aerial photos in the check station or headquarters. Look

hard and take notes.

Just any pond, isolated or

not, isn't necessarily a "glory hole." Ducks have to

have a reason to go there.

Some marsh ponds are located

along traditional flyways and almost always have a fair number

of ducks trading near-yes, ducks have regular travel routes, just

like other animals. But unless a pond offers something to hold

their attention, ducks aren't very prone to work a piece of water.

Usually, food is the best attractant.

The absolute-best marsh ponds

are the ones with growths of native aquatic vegetation. Look for

ponds with thick growths of wigeon grass, spikerush, smartweed,

and other aquatics heavily used by ducks. Find one, particularly

one isolated from other ponds, and you're in business.

But be aware that growth of

aquatic vegetation can vary wildly from year to year, depending

on weather and water conditions. Ponds in some sections of a marsh

seem to produce more vegetation in dry years while others produce

more duck food in wet years.

It was food-a profusion of

wigeon grass-that made that pond mentioned at the top of this

piece so attractive to ducks. The next season, that same pond

produced almost no wigeon grass, and hunting there was pitiful.

But a pond a little farther north and west of that one produced

a bumper crop of spikerush and smartweed. It was the "glory

hole" that season.

Try to learn more than one

public hunting area.

Many of the areas are open

only a few days a week, but managers try to stagger open days

of nearby areas so that hunters have some place to go every day

of the week.

Also, by scouting at least

two areas, hunters have options should weather or other conditions

move birds out of the primary hunting area.

Equipment?

A boat may be the most important

piece of equipment a hunter can have when using public lands.

While it's possible for boatless

waterfowlers to take advantage of the public hunting opportunities,

those without some sort of watercraft are severely limited in

their options. Walk-in hunting is available on only a few of the

areas, and being afoot seriously restricts a person's ability

to get away from the crowd.

While canoes and pirogues can

be very effective on some areas, the most utilitarian vessel is

a wide, aluminum flatbottom skiff 14 to 18 feet long pushed by

a 15- or 30-horsepower outboard.

The shallow-draft flatbottom

can navigate the thin water of low-tide sloughs common on the

coastal marshes; plus, the beamy craft can handle the considerable

load of decoys, dogs and other gear associated with waterfowl

hunting. Too, the aluminum boats can take the beating of rough-and-tumble

hunting.

Decoys?

There is no such thing as too

many decoys.

Most hunters on public areas

use no more than two dozen blocks. Double that, and hunters double

the visibility and effectiveness of their spread.

Yes, it's more work to haul

those extra bags. But it proves the point that those willing to

work harder than the next guy are the ones who see the best results

on public areas.

While mallard decoys work well,

it's a good idea to include many drake pintail decoys in a spread.

Pintails are a common bird on Texas coastal areas (they're much

more common than mallards), plus the white on the "sprig"

decoys shows up much better than the drab of hens, making them

more easily spotted by overhead ducks.

While hunters want their decoys

to be seen by approaching ducks, they don't want those birds to

spot the crouching hunters.

If there's a most-common mistake

made by waterfowlers on public lands (other than incessant and

hideous blowing of duck calls), it's not taking concealment seriously.

Because regulations governing

use of public waterfowl hunting areas prohibit construction of

permanent blinds, hunters must use natural cover to conceal themselves.

Some pond edges offer scant cover, and hunters wanting to set

up there must haul temporary blinds.

But many potholes and ponds

on coastal marshes are rimmed with thick, waist-high growths of

cordgrass. That cordgrass can make a perfect hide, but only if

hunters are careful to not destroy the cover by wallowing out

a huge hole in it.

The best tactic is to pick

a thick stand of cordgrass on the upwind side of the pond (remember,

ducks land into the wind), then very carefully burrow into the

cover, making a hole just big enough in which to sit flat on the

soggy ground. (Chest-high waders are required gear.)

Hunters burrowed in the grass

need to make certain there is enough high cover on their east

side that, when the sun rises, it will keep them in shadows, making

it harder for approaching ducks to spot the hidden hunter.

By remaining still and taking

care not to destroy cover when entering and exiting the burrow,

a good clump of cordgrass can serve as an effective blind throughout

the season.

And if hunters pick the right

ponds-if they scout, learn what ducks are looking for and are

willing to work harder and hunt smarter than the next guy-they'll

find the public waterfowling areas along the Upper Texas Coast

can provide experiences that money can't buy.

Literally.

# # # #

page 1 / page 2

|