Preseason scouting is essential

for successful turkey hunting.

By Matt Williams

Page 2

Why scout?

As a rule, a mature gobbler is a homebody. He has his home range

and normally won't vacate it unless he's pressured out for one

reason or another.

Preseason scouting enables the hunter to pinpoint the whereabouts

of a gobbler before the season opens. By nailing down the location

of multiple gobblers, the hunter can dramatically increase his

or her chances of finding somebody at home when it's legal to

tote a shotgun.

Scouting options

Ask any avid turkey hunter and he'll be quick to tell you that

scouting is hard work. Done properly, it'll result in bleary eyes

and sore feet.

"You've got to get out there early and you've got to cover

lots of ground," stresses Burk. "When I scout, I like

to be at key spots at the key times of day so my chances of getting

a bird to gobble are the greatest."

Burk says the best way to find a key area on unfamiliar land

is to purchase a good topographical map. Maps of the Angelina,

Sabine, Davy Crockett and Sam Houston National forests are available

at the Homer Garrison Federal Building in Lufkin. The maps cost

$4 each. You can order them by writing to 701 N. First, Lufkin,

TX 75901. Include a check to cover the cost of each map, plus

$1 for postage and shipping. The number to call is 409-639-8620. Burk says the best way to find a key area on unfamiliar land

is to purchase a good topographical map. Maps of the Angelina,

Sabine, Davy Crockett and Sam Houston National forests are available

at the Homer Garrison Federal Building in Lufkin. The maps cost

$4 each. You can order them by writing to 701 N. First, Lufkin,

TX 75901. Include a check to cover the cost of each map, plus

$1 for postage and shipping. The number to call is 409-639-8620.

Burk identifies likely spots by looking for creek intersections,

preferably those that are located off the beaten path, away from

roads and other easy access routes. That done, he'll go to the

actual spot and "ground proof" it against the map to

determine if it looks as good in real life as it does on the map.

"There's a simple formula to go by," explains Burk.

"What you need is a fairly open upland site that makes a

gradual transition into an unfragmented hardwood creek bottom.

The best spots are usually on fairly open hillsides - places that'll

enable you to hear a long way."

Burk will sometimes spend a full day or two pinpointing and checking

suspect areas. Once he's nailed down some spots he likes, he

takes his scouting to the next level.

"I like to be at those key places at least 30 minutes before

daylight," says Burk. "From then to about the first

hour after daylight is when the gobbler is going to be most prone

to gobble."

Getting him to talk

Revved up gobblers are apt to gobble at anything - slamming doors,

ambulance sirens, crow calls and owl calls. Burk has even had

them shock gobble at the blast of a shotgun.

The best way to get a gobbler to give himself away early in the

morning, he says, is to tempt him with some aggressive cutting

or cackling, both of which simulate the sounds made by a hen that's

frantically seeking company.

"You can use owl calls, crow calls, screaming peacock calls,

etc., but when I'm scouting, I want to come as close to guaranteeing

a response as possible," Burk explains. "If I don't

get a response with an aggressive cut, he's either just not there

or he's not interested."

In the event Burk's call does get hammered by a resonant blast,

he won't stick around. Instead, he marks the spot on his map with

an "X" and heads out to his next key area.

"That's a mistake a lot of hunters make," he explains.

"They get a response and they can't resist the opportunity

to mess with the bird. They end up calling the bird in and he

spooks, which in turn educates him to the fact that everything

that sounds like a hen isn't necessarily a hen. He's usually a

whole lot tougher to call up the next time around."

Two-wheel drive

The only way a hunter can put multiple X's on his map before

opening morning is to spend a lot of time scouting. In turkey

hunting, that means covering lots of ground.

Many of the national forest roads are accessible to motorized

vehicles. This provides hunters the luxury of being able to drive

around and stop periodically to try and draw a response from the

roadside woods.

While stop-and-go scouting is much easier than walking, it's

not without some pitfalls. The potential problems here are twofold.

First off, there may be 10 other hunters who locate the same

birds you do, and five of them, all toting shotguns, may show

up at the same spot on opening morning. Second, it is very likely

a roadside bird will already have heard every type of call imaginable

by the time opening day rolls around.

"I don't put a whole lot of faith in roadside gobblers,"

notes Burk. "I'd much rather get off the beaten path and

locate birds that aren't very accessible. Find a bird that's a

mile or two from any well-traveled road and your chances of having

him all to yourself on opening morning will be much greater."

While some forest roads are open to vehicles, others are closed

to motorized traffic during the spring to protect wild turkey

broods from disturbance. The only way to access many of the sandy

forest trails is on foot, whereas the more developed gravel roads

may be traveled on foot or by bicycle.

Either way, you'd be advised to try and get into shape beforehand.

Some of the best turkey country in East Texas consists of steep,

sloping ridges and long, sloping hills that'll test the stamina

of a track star.

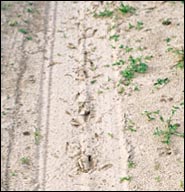

Road signs

It's always encouraging to hear birds on scouting missions. But

visual signs can be reliable as well.

The most obvious sign to look for is tracks. Turkey tracks can

show up anywhere along a sandy trail or road, particularly at

creek crossings and other well-traveled intersections. Find tracks

accompanied by strut marks (the dual marks a gobbler makes when

dragging its wings) and you can rest assured there's probably

a Tom somewhere in the area.

Another reliable sign is droppings. If Burk finds a concentration

of droppings in a food plot, he takes it as a pretty good sign

that the birds are utilizing the plot on a regular basis.

"Find a spot like that and you'd be advised to stab a decoy

in the ground and wait," says Burk. "He's going to show

up there sooner or later."

# # # #

page 1 / page 2

|